Architecture

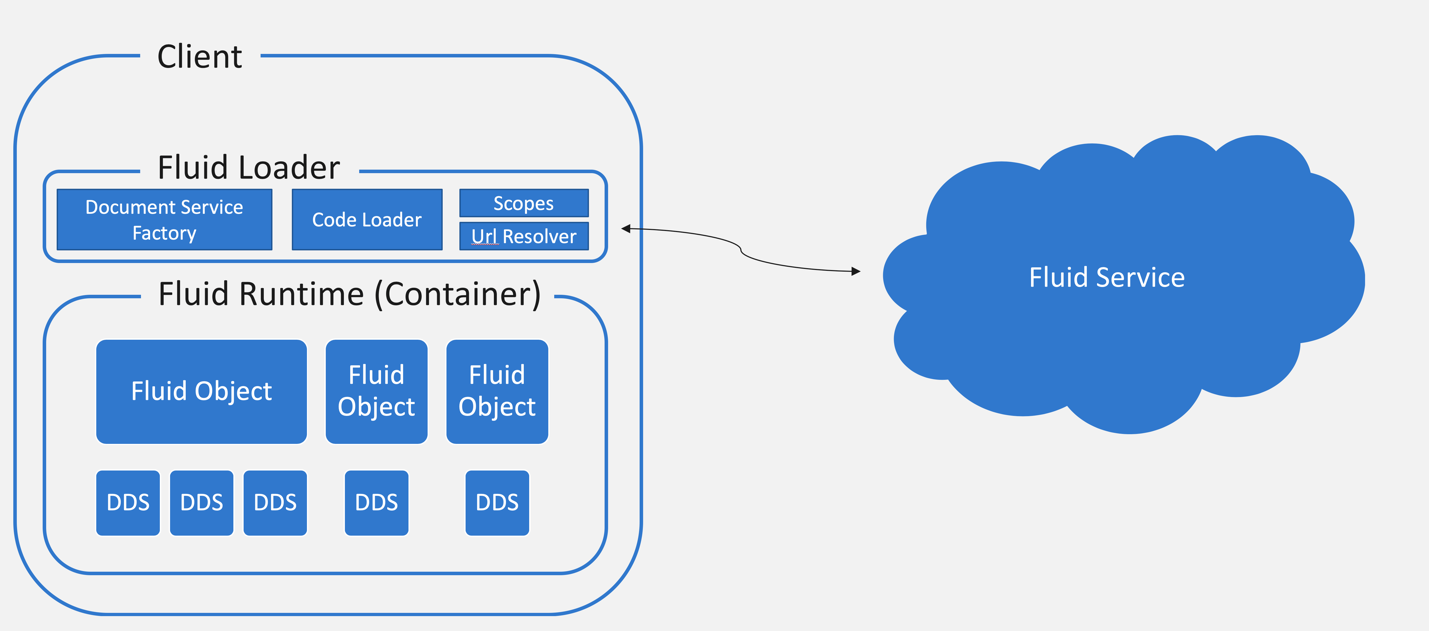

Fluid Framework can be broken into three broad parts: The Fluid loader, Fluid containers, and the Fluid service. While each of these is covered in more detail elsewhere, we’ll use this space to explain the areas at a high level, identify the important lower level concepts, and discuss some of our key design decisions.

Introduction

The Fluid loader connects to the Fluid service and loads a Fluid container.

If you want to load a Fluid container on your app or website, you’ll load the container with the Fluid loader. If you want to create a new collaborative experience using the Fluid Framework, you’ll create a Fluid container.

A Fluid container includes state and app logic. It’s a serverless app model with data persistance. It has at least one Fluid object, which encapsulates app logic. Fluid objects can have state, which is managed by distributed data structures (DDSes).

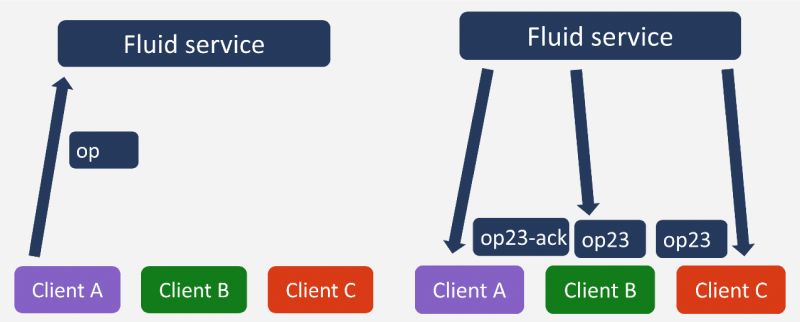

DDSes are used to distribute state to clients. Instead of centralizing merge logic in the server, the server passes changes (aka operations or ops) to clients and the clients perform the merge.

Design decisions

Keep the server simple

In existing production-quality collaborative algorithms, like Operational Transformations (OT), significant latency is introduced during server-side processing of merge logic.

We dramatically reduce latency by moving merge logic to the client. The more logic we push to the client, the fewer milliseconds the request spends in the datacenter.

Move logic to the client

Because merge logic is performed on the client, other app logic that’s connected to the distributed data should also be performed on the client.

All clients must load the same merge logic and app logic so that clients can compute an eventually consistent state.

Mimic (and embrace) the Web

The Fluid Framework creates a distributed app model by distributing state and logic to the client. Because the web is already a system for accessing app logic and app state, we mimicked existing web protocols when possible in our model.

System overview

Most developers will use the Fluid Framework to load Fluid content or create Fluid content. In our own words, developers are either loading Fluid containers using the Fluid loader or developers are creating Fluid containers to load.

Based on our two design principles of “Keep the Server Simple” and “Move Logic to the Client”, the majority of the Fluid codebase is focused on building Containers.

Fluid containers

The Fluid container defines the application logic while containing persistent data. If Fluid Framework is a serverless application model with persistent data, the container is the serverless application and data.

The Fluid container is the result of the principle “Move Logic to the Client.” The container includes the merge logic used to replicate state across connected clients, but the container also includes app logic. The merge logic is incapsulated in our lowest level objects, distributed data structures (DDS). App logic operating over this data is stored in Fluid objects.

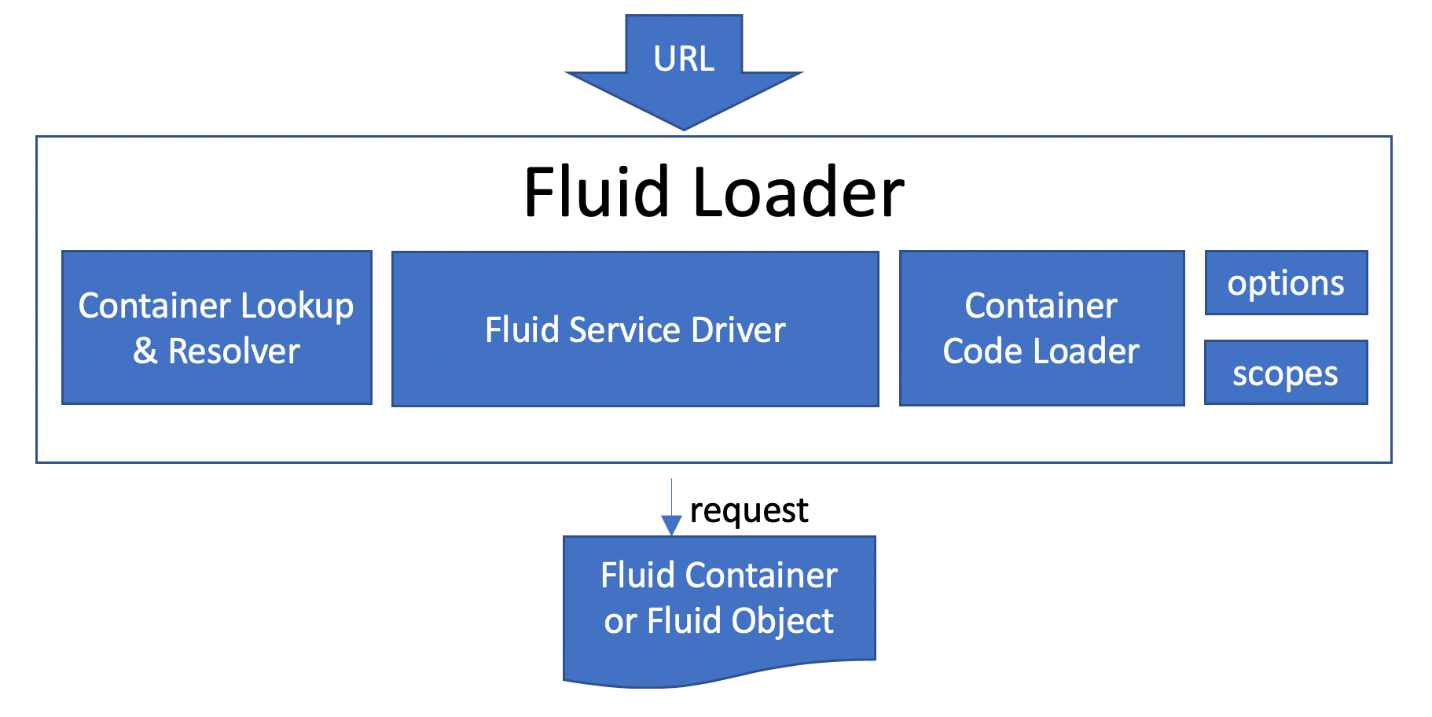

Fluid loader

The Fluid loader loads Fluid containers (and their child Fluid objects) by connecting to the Fluid service and fetching Fluid container code. In this way, the Fluid loader ‘mimics the web.’ The Fluid loader resolves a URL using container resolver, connects to the Fluid service using the Fluid service driver, and loads the correct app code using the code loader.

Container lookup & resolver identifies, by a URL, which service a container is bound to and where in that service it is located. The Fluid service driver consumes this information.

The Fluid service driver connects to the Fluid service, requests space on the server for new Fluid containers, and creates the three objects, DeltaConnection, DeltaStorageService, and DocumentStorageService, that the Fluid container uses to communicate with the server and maintain an eventually consistent state.

The container code loader fetches container code. Because all clients run the same code, clients use the code loader to fetch container code. The Loader executes this code to create Fluid containers.

Fluid service

The Fluid service is primarily a total order broadcast: it takes in changes (called “operations” or “ops”) from each client, gives the op a sequential order number, and sends the ordered op back to each client. Distributed data structures use these ops to reconstruct state on each client. The Fluid service doesn’t parse any of these ops; in fact, the service knows nothing about the contents of any Fluid container.

From the client perspective, this op flow is accessed through a DeltaConnection object.

From the client perspective, this op flow is accessed through a DeltaConnection object.

The service also stores old operations, accessible to clients through a DeltaStorageService object, and stores summaries of the Fluid objects. It’s worth discussing summaries at length, but for now, consider that merging 1,000,000 changes could take some time, so we summarize the state of the objects and store it on the service for faster loading.